Uluru Statement From The Heart: A trek through the paragraphs.

There is a seductive cleverness to the Uluru Statement From The Heart (USFTH).

It flirts disconcertingly with both genius and fraud.

Disarmingly short. Intentionally incomplete. Perplexingly indecipherable.

Conveying a message poised somewhere between hope and disillusion.

Container of hidden secrets, it exposes tantalizing invitations to dig and question. The discoveries enlighten, yet also confuse and obscure.

To plumb the depths of the USFTH you must embrace learning about the aboriginal experience. This is a bewildering labyrinth of history, law, culture, politics, violence, and humanity.

The USFTH strives to solve the heretofore insoluble. A prisoner of its intractable subject matter, it smashes fine intentions and willful enthusiasm into frigidly indifferent reality.

It is sadly, beautifully, defective. A flawed beacon of hope fueled by desperate optimism and poor alternatives.

That doesn't mean it isn't successful.

To understand it, I've tried to explain it. Dispassionately. Objectively. Paragraph by sentence by word.

My results are below.

Paragraph by paragraph.

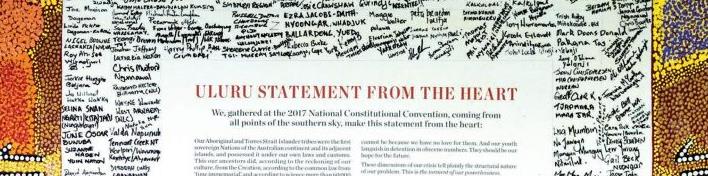

TitleULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

A simple title that speaks of simplicity, sincerity, profoundness, and generosity.

But wait. The game is immediately afoot.

From the heart because it is sincere?

Or because Uluru is the heart of Australia geographically?

Or because this document transcends secular philosophy (Uluru often being considered the "spiritual heart" of local indigenous culture)?

Or all of the above?

The symbolism of 'Uluru' seems critical. The creators of USFTH fought to keep it even when faced with some embarrassing traditional owner objections.

Already we understand the USFTH might defy simple, first glance interpretations.

PreambleWe, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

It wastes no time touting its pedigree. The National Constitutional Convention. That's got to be a fun gathering. Judgmental old white people in wigs and gowns smelling of mothballs, red wine, and learned opinions.

Well, no.

The convention was actually the 'First Nations National Constitutional Convention'.

Something else entirely. Far from being a stuffily august legal gathering, it turns out that lawyers were explicitly excluded1. This convention was composed of representatives from a series of indigenous regional dialogues.

So why drop 'First Nations'?

A preference for brevity? Are the demographics of 'We' contextually self-evident? Or is it an attempt to pad the credentials of the contributing quorum?

The omission is unfortunate, as the precise nature of the creators of the Statement is important.

At worst, this shows a willingness to play fast and loose with words, even though this could foreseeably mislead.

At best, it reveals a certain amateurishness. For the sake of two words, and at such a non-controversial juncture, why open the door for criticism and doubt?

Next up in the same sentence the phrase "coming from all points of the southern sky" asserts both inclusiveness and generality (possibly - I've been unable to find any historical reference for this phrase).

Why not just say "representing all the indigenous peoples of Australia?"

Perhaps a metaphorical flourish adds spiritual depth to the Statement. Maybe it references the cultural connection of the conference participants to the wider firmament.

Or, does its lack of specificity nicely sidestep issues relating to first nations people whose voices were not represented in the process?

Moving on.

Paragraph 11Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. 2This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

Paragraph 21This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. 2This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. 3It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

Paragraph 31How could it be otherwise? 2That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

Paragraphs 1, 2 & 3 all combine to assert past and present ownership credentials. Dedicating three paragraphs to this topic highlights its importance.

The first sentence is a forthright assertion. It leads because it is difficult to dispute.

Most non-indigenous Australians are going to agree with the premise that Australia was once Aboriginal land.

The problem the USFTH has is that the same people also assume that the ownership and control of Australia has now passed from the indigenous peoples to all the peoples of the modern nation.

Not surprisingly, the remainder of the three paragraphs is spent explaining why they are wrong.

Paragraph 1, sentence 2 emphatically and redundantly reinforces the claim "we've been here a long long time". This sentence seems at first glance to be a bit pointless. Is it not enough to agree that the first nations people were in possession of Australia prior to 1788 and then go from there? Apparently not. The argument being advanced is that the mind-blowing length of association has created a sacred spiritual bond that transcends non-indigenous notions of ownership.

The first two sentences of paragraph 2, with their odd italics, and even odder wording, lay out the sacred spiritual relationship. The final sentence of paragraph 2 attempts to guard against any claim that sovereignty has been relinquished by indigenous Australians, or validly terminated by anyone else.

Finally, paragraph 3 serves to drive home the absurdity of any other point of view.

So,in point form, the argument is this:

- Our original ownership is uncontested (para 1).

- We've been here forever, thus have a sacred link to this land (para 2, 3).

- We've never given up (ceded) ownership (para 2).

- Our ownership has never been taken from us (extinguished) (para 2).

- Our ownership is different anyway (spiritual), and at the very least, coexists with your ownership (para 2).

There is a lot to unpack in these three paragraphs!

Taken individually, from a non-indigenous perspective, each of these claims seem refutable (or irrelevant).

Yes, you've been here a long time, but so what? If I own a house and the bank forecloses on it, it doesn't matter if I've had it for 1 year, or 50 years - I'm still on the street. And how long is long enough when it comes to this sacred ownership-by-virtue-of-ancestry business? How many generations of my forebears have to be born in Australia before I can claim a spiritual ancestral tie. One? Five? Ten? A thousand? Who sets that number?

The sovereignty "has never been ceded" argument is probably supportable if you read it as "has never been willingly ceded". This is a bit irrelevant. Cession does not always require consent. Human history is a continuum of lands that were not voluntarily ceded in any way, yet still ended up owned by other parties. Conquests, civil wars, and plain old compulsory land acquisitions will all do the trick. You don't always get a say. IANAL, but (given the ipso facto realities of Australia today) the claim that ownership has never been ceded or extinguished seems problematic.

The claim of co-existence of sovereignty with the Crown is above my pay grade. One of the problems with having such a succinct Statement is that no argument/evidence/example is offered in support of the various claims. It does not help with interpretation. What does "a spiritual notion of sovereignty" actually mean in practice?

So, do the claims in support of indigenous sovereignty when taken as a whole, outweigh the individual refutations? Is the popular catch cry "always was, always will be" more than just a provocative rallying slogan?

I've tried to tease apart the claims made, but it's also worth looking at the wording and style.

What is with the italics and the weird legal style of therefrom, thereto, and thither (para 2)? You might guess that the italics indicate a definition, a quote, or an import of information existing somewhere else. That wouldn't be unusual. It is a bit unusual not to make the source of the words clear (more on this soon).

The section "… a spiritual notion … of sovereignty …" (para 2) is from the 'International Court of Justice in its Advisory Opinion on Western Sahara (62) (1975) ICJ Rep, [85]–[86], as quoted in Mabo v Queensland [No 2] (1992) 175 CLR 1 [40]'.

It makes intuitive sense that the USFTH might pay homage to the famous Mabo case. But why choose a quote that traces back to Mr. Bayona-Ba-Meya, a high ranking official in the kleptocracy of the noted human rights violator Mobutu Sese Seko?

This is all a bit ... weird. But does the original provenance and context of the quotation really matter? Others might disagree, however I'd argue that if the message is solid then the shady backstory is not that important. What frustrates me is the lack of foresight by the USFTH authors. Why create a sideshow when none is required? There are other ways of crafting the same message.

You may be wondering how I know the italicized section is a quotation, and where it comes from. It seems that in order to create a message of acceptable length, the authors decided to leave a lot out. This is unfortunate because it means that people like you and I have to dig around for context and guess at intent. Perhaps one day one of the authors will release an annotated version. Until then we'll have to make do.

Some of the "fine print" for the USFTH can be found in related documents. Megan Davis (one of the key crafters of the USFTH) states "[the Uluru Statement is] actually [about] 18 pages … people only read the first.".

What?

It seems she is referring to the Final Report of the Referendum Council which was released alongside the USFTH, and contains the USFTH. It's not 100% clear, as this report is a lot more than 18 pages. Regardless, this document fills in some of the blanks in the USFTH one pager (and adds a few of its own). It indicates that the words in italics are quotations, and lists the sources. They are not necessarily word for word, so perhaps it is more accurate to say they are "inspired" by the originals.

To close out the section on ownership credentials I'll end with a look at paragraph 3.

"How …? …possessed a land for sixty millennia …sacred link disappears …in merely …two hundred years?"

The purpose of this paragraph seems to be to emphatically end the section with some unimpeachable logic.

The problem is that the logic is crazy bad.

Just because something has existed in a certain state for millennia does not mean that change can't happen. Dinosaurs roamed the planet for 165 million years. Their reign came to a decidedly abrupt end. Peoples can, and do, go extinct. More relevantly, people can, and do, change - for many reasons. Entire cultures have disappeared. So 'sacred links' can disappear. And it's not always a bad thing.

I'm not arguing that is the case here. I'm questioning the wisdom of including the paragraph. If you are going to pose rhetorical questions, make sure your audience can't come back with your least favourite answer.

As an aside, if you want to hear paragraph 3 spoken with the forcefulness its presumed (but unacknowledged) creator intended, check this video.

Time to move on to the next paragraph.

Paragraph 41With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

This "ancient sovereignty shining through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood" is my favourite part of the document so far (other than the title).

I instinctively like the positivity of it.

Can I say what it means? Maybe. Given it's placement after the assertion of ownership (paras 1 to 3), I'm thinking paragraph 4 says "Oh, BTW, our sovereignty is actually a good thing for the rest of you".

Not disagreeing, just need more info. Some explanation of "why" would be helpful.

But what is with the the "substantive constitutional change and structural reform"?

It is just parachuted in here without

- explanation of what it is,

- what it will achieve,

- what alternatives there are, and

- why this is the best option.

This, maybe more than any other part of the document, signals that the USFTH is heavily incomplete.

Ok. Next!

Paragraph 51Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. 2We are not an innately criminal people. 3Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. 4This cannot be because we have no love for them. 5And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. 6They should be our hope for the future.

The word I am drawn to in paragraph 5 is 'obscene' (Sentence 5). It well matches the entire shameful situation.

Only the most empathy bereft person could fail to be affected by these six sentences.

The purpose of the paragraph? It is a call for help, but it is more than that.

The key sentence is "This cannot be because we have no love for them".

Decoded, this sentence reads "In our current circumstances, we are powerless to solve our problems". The implicit subtext is "We need the actions demanded in this document to change that".

Paragraph 61These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. 2This is the torment of our powerlessness.

Paragraph 6 seems to confirm the interpretation of the previous paragraph. But it goes a bit pear shaped.

As much as I love the phrase "the torment of our powerlessness" in sentence 2, and the shout out to WEH Stanner, I can't get past the missing links in sentence 1's logic chain.

"dimensions ... tell plainly the structural nature ...".

"Dimensions" could be inferred here to mean scale/size/magnitude, but I would expect then the preceding word to be 'The', not 'These'. I am leaning, contextually, to it actually referencing "different aspects/axes". In other words "The nature of our crisis tells plainly the structural nature ...".

If the former, there is a big leap from "We're really suffering" (dimensions of our crisis) to "so obviously it's structural".

If the latter, given the preceding paragraph describes symptoms not causes, there is an equally big leap to "so obviously it's structural".

The USFTH seems to consider the causes of indigenous disadvantage to be self-evident. Many non-indigenous Australians will have their own views (wrong or right) about indigenous disadvantage, and the proposed solution may seem illogical, or worse, counter-productive. It surprises me that no attempt is made to justify the appropriateness of the demanded remedy.

At the very least, why not explain what is meant by "the structural nature of our problem"? Sentence 2 seems to point to an answer. "[The] structural nature of our problem ... is the torment of our powerlessness." Logically, one might assume that the source of the quote holds an answer.

In the source, Stanner's essay "Durmugam, A Nangiomeri" (a highly recommended read BTW), the torment of Durmugam's powerlessness was a Catch-22 situation where Australian law could not address his grievance, yet outlawed the customary payback solution native law provided.

Indeed, this dilemma does seem 'structural'. An unresolvable inequity was intractably embedded within the governing legal system. Clashes between Australian common law and Indigenous Australian customary law may be one small part of the root issue here, but it is probably not what the USFTH means by "structural".

With no specific direction from the USFTH this must be conjecture, but it seems likely that the structural issues referenced relate more to self perpetuating intergenerational disadvantage.

Paragraph 71We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. 2When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. 3They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

Paragraph 4 ("With substantive constitutional change and structural reform...") hinted at demands. These now become more explicit.

Quoting Gough Whitlam's words ("rightful place") supports the Statement with noble intent, but invites needless questions.

When reading the USFTH you can feel the emotional investment of its authors. There seems to be a desperation to artfully sculpt a text that can one day be judged worthy alongside the great documents of history. If the authors can do that, and achieve their primary aims, great. But if they fail at the latter, the former is lost as well.

In this instance the use of "rightful place" favours style over substance. It seems unnecessarily interpretable, opening an avenue for doubters to exploit. Why not "an equal place", or "a productive and contributing place"?

There is no mention of why 'constitutional reforms' are the preferred remedy, or why this is expected to work.

Sentences 2 and 3 "...children will flourish ... walk in two worlds ... gift to their country." is a fabulously phrased and beautiful sentiment. But are literary accolades really the main game here? I would have tried to emphasize the message rather than the writing. Perhaps "When this happens the whole country will benefit."

Paragraph 81We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Straight forward enough. The autological nature of 'First Nations Voice' gets it a pass here. I'm intentionally going to leave aside any discussion of "The Detail" of the 'First Nations Voice'. That is a topic for another day.

It is interesting that more formal, and usual, mouthful-of-descriptive-terms like "National Indigenous Peoples Parliamentary Advisory Council" were avoided.

Was this a conscious effort to break with the historical ways of doing business? Is this about trying to be more accessible to everyday Australians?

It is catchy and descriptive.

Paragraph 91Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. 2It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

Australia is built on Aboriginal names. I love being introduced to the word 'Makarrata'. Not quite as excited about the literal translation2 mind you. Using an Aboriginal term here makes me wonder why they didn't do the same for "Voice"? I might as well point out that in this paragraph (unlike elsewhere) the italics seem to be used to signify a definition rather than a quote. While the stated source (Galarrwuy Yunupingu, ‘Rom Watangu’, The Monthly (July 2016), 18)3 does talk of an instance of Makarrata (describing it as a peacemaking event), there is no trace of the words "the coming together after a struggle".

Paragraph 101We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

This document has a weird tension between trying to be simple and accessible, trying to represent deep grievances and demand change, while not testing the good-will of the intended recipients. Here they went with "agreement-making" rather than the potentially flammable "treaty" (which features very heavily in the accompanying Final Report4), presumably for this reason.

So in summary, the asks in this document are:

- First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution

- Makarrata Commission (for treaty, and truth telling)

Oddly, the accompanying Final Report also has two asks (Recommendations, pg 2).

- First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution

- Extra-constitutional Declaration of Recognition

It goes on to "additionally ... [note a] matter of great importance ... as articulated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart ... a Makarrata Commission". Then it backs heavily away from it. "[Can't make] ... a specific recommendation on this ... [not in] our terms of reference ... various state governments [already] engaged in agreement-making."

Why is the Makarrata Commission featured in the USFTH when it is only tepidly supported in the Final Report? One assumes there is politics involved. 'Treaty & Truth' had to be prioritized in order to honour the wishes of the participants of the regional dialogues, but for some reason this was toxic within the actual Final Report. Was the solution to feature it in the USFTH and hope that public opinion carried it to government anyway?

Why is the explicitly recommended Extra-constitutional Declaration of Recognition not mentioned in the USFTH? Did the Dialogue Participants think it pointless symbolism? Did the Referendum Council members consider it a non-controversial and achievable aim? Is it included because it is an "easy win"?

Paragraph 111In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. 2We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. 3We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

Finally, the call to action. I particularly like the reference to the 1967 referendum. It frames this effort as a natural continuation of that (successful) initiative. Clever. I also like ending with the imagery of setting off on a joint endeavor. "Base camp", with its mountaineering connotations, is a bit incongruous in an Australian setting. There seems to be a slight mixing of metaphors, but whatever.

Final thoughts

Six years after it was released, it is easy to forget the revolutionary nature of the USFTH. There is a breathtaking audacity in the presumptuousness of this document. The process on which it was founded could not have foreseen such a result. Decades of precedent would have expected yet another boringly bureaucratic A4 stack of carefully cross referenced facts and recommendations. It ought to be gracing the dusty shelves of some parliamentary library. Politicians and policy wonks should now be using it to cherry pick particular recommendations on an as-needed basis.

By creating a single page manifesto, and masterfully orchestrating the propagation of an "invitation/gift" narrative, its creators bypassed protocol and took their message mainstream.

The document can be criticized. And it should be. Its composition does not live up to the aspirations of its creators. It contains questionable logic. It has massaged truths, omitted critical considerations, and downplayed others.

Its power is in its perceived accessibility, and in its emotional gravity. Any person can pick it up and read from top to bottom. Perhaps many will think they understand it. My own experience with it tells me they likely won't5, but this may not be important. If they are compelled to further engage, its aims are likely met.

I hate to concede that this document is a success. At the nuts and bolts level there is too much to dislike about it.6

The results, however, speak for themselves. Australia appears to be headed for a showdown sparked, in no small part, by this document.

What role does it have yet to play?

For me, the USFTH does not answer the personal question of how to vote in the Constitutional Referendum it has inspired.

What it does do, is galvanize an imperative to understand the meaning of that vote.

As Pat Anderson, Co-chair of the Referendum Council, has succinctly stated "You have to inform yourselves. It doesn't matter in the end which way you vote, but do it with some consciousness, with some heart, and with some intellect."

Megan Davis: the other group we banned were lawyers ... they tend to be know-it-alls ... so we just we banned all the lawyers↩

"Makarrata literally means a spear penetrating, usually the thigh, of a person that has done wrong…" - Merrikiyawuy Ganambarr-Stubbs.↩

"Rom Watangu": Included as Appendix D in the Final Report of the Referendum Council↩

'Treaty' is mentioned 96 times, 'Agreement-making' is mentioned 35. The terminology seems to depend largely on the audience referenced/targeted.↩

I've given up counting the hours it has taken me to scratch the surface.↩

Could I do any better? Dunno, but I have tried......↩